That pesky age discrimination law (again)

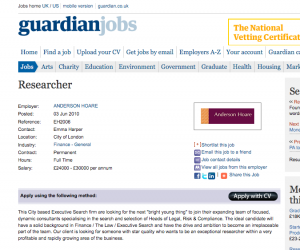

In January I noticed not all employers had yet “got it” about age discrimination. Now here’s more evidence, this time from an “executive search” company no less:

I suggest if they want to avoid breaching regulation 7 of the Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006, they should consider also looking for the next “bright middle-aged thing” or even a “bright old thing”.