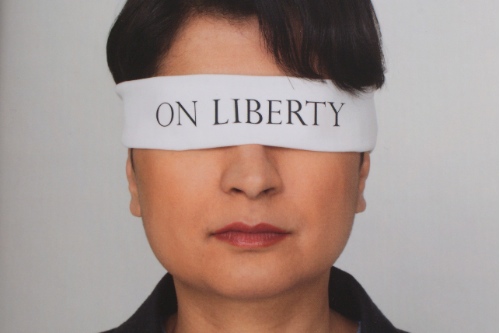

Liberty’s director is a great communicator, both in front of an audience and in the media; and partly because of that, this book is a little bit disappointing.

Liberty’s director is a great communicator, both in front of an audience and in the media; and partly because of that, this book is a little bit disappointing.

The jacket calls On Liberty a “frank and personal book” and there are flashes of the personal about it. Chakrabarti talks to some extent about her son and her parents, this perhaps being the most striking passage:

That evening my father’s words captured my imagination and turned my stomach and it makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up even today as I write. I duly reconsidered and never looked back. If I went on in adult life to be the bugbear of so many authoritarian men, they only have one of their own number – my dear old dad – to blame.

She also mentions a number of her friends. But the personal angle is pretty restrained, actually: on that, I agree with Gaby Hinsliff. For the most part On Liberty is the sort of polemic you’d expect from the country’s leading civil liberties campaigner. It reads as though it’s adapted from speeches of the kind Chakrabarti must often give, on Liberty’s usual themes: torture, ASBOs, detention without charge, DNA, secret courts and so on – and this is I think its main weakness in both style and substance.

First, style. Jokes and asides that work well with an audience –

Let’s face it – if you really think there are only fifty shades of grey, you probably need a bigger box of crayons.

can be a bit clunking on the page. Sam Wollaston says the book’s “more lawyerly than writerly”; I’d say the feeling that Chakrabarti’s argument builds within rather than across chapters, together with her use of fairly familiar turns of phrase on the whole, makes the book more “speakerly” than anything.

In terms of substance, I hoped Chakrabarti would range widely on freedom generally – but she pretty much sticks to the day job. There’s not much discussion of freedom of expression, for example, a key aspect of liberty but not one Liberty is known for being strong on. In one short passage she says

Speech is often described as an absolute right in other parts of the world but it can never be absolute in practice

which is fair enough. Later in the content of freedom of religion she mentions the 2004 controversy over the closure of the play Behzti by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti (which I don’t remember Liberty taking a strong public stance about at the time). But there’s not a lot else.

One thing the book does reveal about Chakrabarti’s wider political thinking – I would have liked much more of this – is that the evils of discrimination are just as important to her as liberty in the usual sense.

Lawyers can number, translate and contest the application of our rights to particular circumstances. But these values can be summed up by three little words: dignity, equality and fairness. These are the ideas from which our various human rights flow and for reasons this book explains, the greatest of these is equality.

I’m not sure the book does explain that, but Chakrabarti’s feelings about discrimination do come to the fore repeatedly.

Towards the end she makes clear she imagines a variety of readers, and that you may be “supportive, sceptical or downright seething”. I doubt this book will make many people seethe, but I’m not sure it will persuade many sceptics either. Chakrabarti identifies what she calls “tock-tick logic” (rationalising your instinctive preferences after the event) – and to be fair she makes no claim to be freer of it than anyone else – but she seems to do something similar with prisoners’ votes:

Wicked prisoners shouldn’t have the vote. Really? Not any one of them, no matter how short the sentence or questionable the crime? What if you chose to go to prison rather than take the identity card forced on you by a future authoritarian government?

… is this the issue over which you would throw the baby out with the bath water and give up your own rights with those of the prisoners?

I don’t doubt Chakrabarti would care about this anyway. But would she marshal so many arguments in favour of the policy merits of prison votes, were this not a totem issue on which liberals’ instinct is to defend the European Court of Human Rights? Her answer to the “ticking bomb” scenario is a good one, but not many thoughtful Liberty-sceptics will have disagreed with her on it anyway.

For the most part her critique is rigorously moderate, but on rare occasions she’s tempted into overstatement to make a point. Just as Chakrabarti’s reaction to Theresa May’s Conservative conference speech called the Home Secretary’s admittedly repressive proposals on extremism “state powers worthy of a caliphate” at one point in On Liberty she compares our own religious history to the Taliban’s Afghanistan:

The first option is to pick a religion, any religion. Make it your favourite, to the extent of embedding it into the fabric of your society, and legal and political systems. Everything else is secondary, even subordinate – in fact, ruthlessly so. The extreme modern example might be Afghanistan under the Taliban, but another illustration might be Britain, and not so very long ago.

That seems to me a reasonable comparison if by “not so very long” ago she means a few hundred years. She implies Britain’s not an extreme example, true; but when did we last subordinate everything ruthlessly to one religion?

For a cover price of £17.99 in hardback (of course you may be able to buy it at a discount) you only get about 150 pages of actual book: reprinting the Human Rights Act takes up thirty pages at the end. So my disappointment’s a bit about quantity, I must admit.

If you’re not just a fan of Shami Chakrabarti but agree with her public campaigns, want to read about exactly those issues and along the way find out just a tiny bit more about the woman herself – then you’ll love this book. She does as always make a passionate and pretty strong case for her beliefs. But I wish On Liberty were wider-ranging, or more surprising.

On Liberty, by Shami Chakrabarti, is published in hardback by Allen Lane on 2nd October 2014, priced: £17.99

Carl Gardner2014-10-01T19:00:34+00:00

Leave a comment