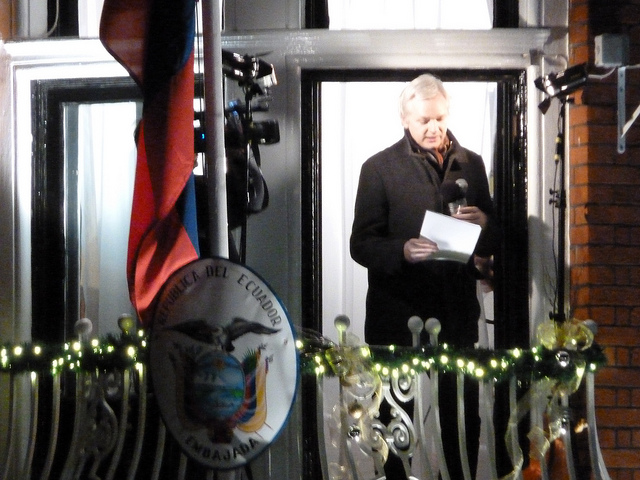

It’s a year since Julian Assange’s extraordinary decision to seek refuge in Ecuador’s London embassy. What should be done about him?

The government has three broad options: it can try to de-recognise Ecuador’s embassy or break off diplomatic relations and close it, so that police can enter the embassy building and arrest him; it can make some sort of deal with Julian Assange – letting him go to Ecuador or giving him some guarantee; or it can let the police continue their stubborn watch for another year or more.

I wrote last year advising ministers against withdrawing the Ecuadorian embassy’s diplomatic status – and my view hasn’t changed. True, the Diplomatic and Consular Premises Act 1987 does indeed give ministers a domestic power to withdraw recognition. Section 1(3) says

In no case is land to be regarded as a State’s diplomatic or consular premises for the purposes of any enactment or rule of law unless it has been so accepted or the Secretary of State has given that State consent under this section in relation to it; and if—

(a) a State ceases to use land for the purposes of its mission or exclusively for the purposes of a consular post; or

(b) the Secretary of State withdraws his acceptance or consent in relation to land,

it thereupon ceases to be diplomatic or consular premises for the purposes of all enactments and rules of law.

But as I said last year, withdrawing consent under section 1(3)(b) would be legally risky, and might not work. Julian Assange or Ecuador could well succeed in a legal challenge to the decision (on the basis that arresting one man is not the sort of purpose for which Parliament granted the power), in which case Britain would be left looking pretty silly. I doubt the government will want to hand Assange the legal initiative, or risk giving him a legal and public relations coup. And this is without even mentioning the diplomatic consequences worldwide of such a decision.

One day, Assange may become such an irritant that de-recognition becomes a risk worth taking (actually it’d be legally safer I think to break off diplomatic relations completely and close the embassy). But I think that day’s long off.

The second option is to do some sort of deal with Assange, either unilaterally – no, I really mean bilaterally, don’t I? – or together with Sweden.

The first is surely unreal. Letting him go to Ecuador, or freeing him here with a promise not to extradite him, would breach the UK’s legal obligations to Sweden at a time when other EU member states know Britain will soon want to opt back in to the European Arrest Warrant system (assuming it formally opts out of EU justice measures as whole, as expected). Why should the Commission or other member states accept Britain’s opt-in, or any changes Britain may want to the European Arrest Warrant system, if it’s failing to fulfil its obligations anyway? Bigger things are at stake for Britain than this one case alone. A deal excluding Sweden makes no sense.

So what about an agreement involving Sweden?

There could in theory be an agreement that Assange be questioned where he is, by videolink or by Swedish prosecutors attending on him in Knightsbridge. But why should they agree to that? As I understand Swedish criminal procedure they would normally, in a rape case like this, have their suspect in custody for final questioning at a late stage in their investigation and a decision on formal accusation – after which the trial must by law begin within two weeks. Interviewing Assange other than on her own patch may disadvantage the Swedish prosecutor in ways not obvious to foreign observers – she may not be able to exercise legal powers relating to her questioning, for instance. And what guarantee would she have that following questioning he would come to Sweden for trial? Or that even if he were tried in his absence, he’d surrender himself for imprisonment, if convicted? No: it makes no sense for Sweden to agree to this. And, by the way, even if Assange agreed to serve any prison sentence in Britain – what would stop an American extradition request from here?

That leaves either an agreement involving a guarantee by Sweden that he wouldn’t be extradited onwards to the US; or a guarantee by Britain that it wouldn’t give consent to onward extradition under article 28.4 of the European Arrest Warrant Framework Decision.

Neither the British government nor, I think, Sweden’s, can agree in advance to rule out onward extradition entirely. As far as Britain is concerned, if it surrendered Assange to Sweden and was then asked for its consent to onward extradition, under section 58 of the Extradition Act 2003 the Home Secretary would need to apply a staged series of legal tests before, finally, exercising a discretion whether to consent. The government may have the final say, but it cannot lawfully make an advance decision in the abstract without sight of an actual request, without any consideration of the merits and without respecting the process laid down by Parliament – yet purporting to bind future governments – that Britain would never consent to Assange’s further extradition in any circumstances whatever.

As David Allen Green has written, the position seems, unsurprisingly, similar in Sweden in respect of onward extradition to the US. In neither country can ministers legally purport in advance to take a final, binding decision on a hypothetical request (and in Sweden’s case, before the courts had even looked at it as they’d be required to).

And by the way: the guarantee Assange would need is indeed a wide guarantee ruling out any sort of onward extradition at all. You might I suppose argue that a limited guarantee could work – say, that he won’t be extradited to the US for any offence connected with his work for Wikileaks. But if the US really is trying to get Assange “via Sweden” as is often argued (an argument I’ve never thought made sense, since onward extradition would need British consent – the result being that he’s actually somewhat more protected in Sweden than in Britain) then it can also seek him “via” any other country that doesn’t offer him a guarantee. So any agreement only makes sense for him if it rules out onward extradition anywhere.

Nor does it make sense to limit the guarantee in respect of the kind of offence for which he could be extradited. If, as is sometimes argued, the Swedish rape investigation is some sort of ruse to get him to the US, then an alternative ruse could be dreamt up – an accusation of murder, or drug trafficking, or terrorism.

No: Assange would only be safe, using his own arguments, if a complete guarantee were given against any onward extradition from either Sweden or Britain to anywhere, for anything, ever. Given that neither country knows what offences he (or any other individual for that matter) may have committed or may commit in future, and given that each country must process any future extradition request on its merits, in accordance with its own domestic laws and international obligations to other countries (including the United States) it follows that neither can give the sort of assurance Assange would need. An agreement is impossible.

What, then, are we left with? The cost of the police operation outside the Ecuadorian embassy is reportedly over three million pounds a year. But three million is a relatively trivial sum, weighed against the political cost, for Britain, of backing down. Twenty years of this might cost a hundred million. Still, in my view, the cost of abandoning the extradition of Julian Assange would be greater. If I were William Hague, I’d mentally insure for more.

As well as damaging relations with EU countries and with the US, backing down would encourage those who have political connections in countries with hostile attitudes to Britain – like Iran, a possible future Taliban-led Afghanistan, or even Argentina – to try to defy British justice as Assange has done. And it would embolden regimes that wanted to play the same sort of political stunt that Ecuador has tried here. The attempt Parliament made, by enacting the Diplomatic and Consular Premises Act 1987, to warn rogue states off abuse of their embassies would have failed. It could lead us back the the days of the “Libyan People’s Bureau”.

Britain’s only real option is to doggedly pursue arrest and extradition, however long it takes. Time is, after all, on its side: Assange or Ecuador must tire of this eventually, and a change of regime in Quito could mean the police are welcomed in. I expect the “legal working party” talks that have been announced are, from the British point of view, simply an exercise in trying to persuade Ecuador to give up.

Assange has apparently talked about holding out for five years. The government should prepare to hold out for much longer than that. Any prison sentence Julian Assange might serve – if convicted of any offence in Sweden – is only delayed, and he only gets older, with every year that goes by. He’s just one year older now.

As for what he should do: he should surrender himself to British and Swedish justice.

Carl Gardner2013-06-19T10:02:42+00:00

What should “being able to exercise legal powers” mean? Haven’t you heard that even a Swedish Supreme Court judge Lindskog said questioning abroad is completely legal and the prosecutor had said the opposite in 2010.

If you followed the Manning trial you would hear “WikiLeaks” and “Assange” every day. Why don’t you acknowledge the risk of extradition to the US?

and: next time don’t hide your contempt for Assange so well.

Superb post.

A fourth option may be to encourage the Swedes to come to London for his questioning. This, however, would only mean that the same stalemate would then occur if he was to be charged.

Ignoring Eu politics & the direct effect, the price of following a course of action isn’t always visible or cash. I imagine the price paid so far is above the initial estimate. I’d also hazard a guess that the eventual price will turn out to be more than you contemplate, if not already, and that Hague may, in retrospect, regret paying it when & if he wakes up to what he & his fellows have paid.

I could be wrong, but it is unlikely:)

If you assume the UK would not back down on a change of government, why assume Ecuador would?

Much is speculated on the reasons why the Swedish prosecutor doesn’t use her discretion and question Assange in London (or via video link). None of these speculations are contentious. Why not also speculate on why the prosecutor doesn’t give such non-contentious reasons for not questioning Assange, as you have done? Even Lindskog didn’t think it necessary to speculate as you have, and instead chose to express his mystification over the prosecutor’s reticence. Should not a wider-ranging Swedish perspective (such as Lindsog’s) be taken into account to give depth (and some weight) to your speculations?

You state that Assange may become enough of an irritant that embassy de-recognition becomes a risk worth taking (despite the international furore that would accompany). But what in your view would such an irritation be? It isn’t the costs involved, as you state it’s worth it.

You state that Assange defies British justice but do not cover the reasons why defiance became a legal (rather than belligerent) option for him. Covering this side of the process would allow for human rights and political issues to be presented and would have reasonably allowed equivocation on what Assange “should do”. As this aspect is neglected, your speculations and final opinion can’t represent an adequate appraisal of a much deeper and complex issue. And this does not even cover the sovereignty issues that would come up should Assange be elected to the Australian senate….

@fusako:

I don’t feel contempt for Julian Assange. And I thought I mentioned the possibility of extradition to the US quite a lot!

Questioning abroad may be legal – I didn’t say it wasn’t. But the fact that it’s legal doesn’t necessarily mean it’s reasonable to expect.

On the point about exercising legal powers, I don’t want to speculate on the investigation of the offences Julian Assange is suspected of. I don’t think that’s in the interests of justice or of anyone involved. But taking a British example, a policeman who arrests and questions you may, because of that, have power to search you or your premises, take fingerprints or samples, seize documents and so on. It may be (I don’t know) that there are some special legal powers the prosecutor may wish to exercise that she would be unable to, were the interview conducted in an embassy in London.

@David,

Thanks.

I agree – I think questioning in Knightsbridge is a dead end, too. How could the Swedes be assured he’d surrender himself for trial, or if found guilty? On the basis of his own argument about extradition to the US “via Sweden”, he wouldn’t want to.

@Dean,

Are you just talking about a financial cost?

@Giovanni,

I don’t assume Ecuador would back down on a change of government. I said it could.

I’m not mystified by the Swedish prosecutor’s wish to have Assange arrested and returned to Sweden. That seems to me to be normal. I’m not mystified why she might not want to give reasons, either. Why should she?

I don’t know what might make it worth using legal means to force Assange’s departure from the embassy – say, by de-recognising the embassy under the 1987 Act. I just mentioned it as a remote possibility one day. If I were advising the government nowadays, I’d strongly advise it just to sit and wait.

I don’t follow your point about defiance being a “legal rather than belligerent option”.

I don’t think Australian senators are immune from arrest in Australia, are they? Never mind here. I don’t think there’s any difficult issue about sovereignty. It’s be a problem if there were: I think I agree with many supporters of Julian Assange in wanting politicians to be accountable if they commit crimes – not to be given special legal immunities.

U forgot another option: The Swedes could agree to send him to Ecuador after legal proceedings in Sweden are over. Why insist that a possible US extradition request is dealt with by Sweden? Let Ecuador deal with that.

BTW the UK has also abbandoned the extradition of war criminals like Pinochet, child molesters like Sullivan and terrorists like Quatada without much loss of face or trust in their legal system. Surely JA isn`t WORSE then those guys in your mind? Though it seems that u think he is….

“I don’t assume Ecuador would back down on a change of government. I said it could.” … You assumed that the UK would not back down but Ecuador might, That’s not parity. Why?

You are not mystified about a Swedish prosecutor’s position from a UK perspective, but a Swedish HC judge is. Why are you more certain of the prosecutor’s stance when Lindskog is not? Is that irrelevant?

“I don’t know what might make it worth using legal means to force Assange’s departure from the embassy” … Does your response mean that you can’t see a situation where Assange could be irritating enough to trigger this scenario? Then why even mention this at all? It dilutes your speculations.

It’s not clear whether you see Assange’s seeking of asylum as a valid and legal option rather than petulant defiance. Or do you see the pursuance of any legal option as a form of defiance? Also, do you feel Ecuador have no argument to make that would give the UK a legal option that overrides their EAW commitments? If you are certain of that, what makes you certain?

Your point on immunity was not questioned. The point alluded to was about the pressure governments place on each other that allow otherwise unexplored options to become relevant. You obviously see governmental face-saving is an important aspect in the stalemate (and encourage it also). Do you reckon that there are no sovereignty issues involved or that additional political pressure would be applied to this case if Assange were to be elected to the Senate?

Szsanne,

I don’t insist that a US extradition request is handled by Sweden. If there is ever such a request (I have no idea), it’ll have to be dealt with by whatever country’s he’s in at the time. The UK could receive one tomorrow, and would have to deal with it.

If you think about it though, allowing Assange to go to Ecuador would make no sense at all from the Swedish point of view. If he’s tried and convicted of any offence, then it’d be entirely legitimate for the Swedish prosecutor and courts to want him to serve whatever sentence he might receive in Sweden. Not to allow him to be released to wherever he wants to go.

It’s not a matter of whether Julian Assange is “worse” than any of the people you mentioned. I presume him innocent. Extradition is not a penal measure applied to someone because you’re think they’re guilty or bad.

The point you make about Pinochet is a fair one: the British government decided not to extradite him.

But your mention of the others isn’t fair. The UK government did not abandon the extradition of Shawn Sullivan: extradition was approved by the government, but blocked by the High Court. Julian Assange also argued his case in front of three British courts. A key difference is that Julian Assange is not at risk if tried in Sweden of indefinite detention in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights.

As for Abu Qatada, if there’s one thing the British government has certainly not abandoned, it’s their long attempt to deport him.

Giovanni,

I don’t think my piece did “assume that the UK would not back down”. I doubt it will, because it has legal obligations not to, and because backing down would have serious diplomatic and political consequences. I think that’s a reasoned argument about why Britain can’t, won’t and/or shouldn’t back down. Not an assumption that it won’t.

Ecuador is in a different position to the UK, since it has no legal obligation to any other state here. It may have legal obligations towards Julian Assange. But apparently similar legal obligations towards Aliaksandr Barankov didn’t stop him being arrested. He would have been extradited back to Belarus had the Ecuadorian court not intervened.

So there do seem to be more constraints on Britain’s action than on Ecuador’s.

I’ll look up what Stefan Lindskog has said.

I don’t agree that mentioning the possibility of de-recognising the embassy “dilutes” my post. Excluding all mention of it would have made it incomplete. But you’re welcome to your view of course. And to write your own piece, if you don’t like mine!

I can’t currently imagine what would make this a good option, but that doesn’t mean I can’t imagine that such circumstances might arise.

Julian Assange was on bail, and had a legal obligation to surrender himself to the UK authorities – so I don’t think it’s easy to take the line that his stay in the Ecuadorian embassy is strictly lawful.

No, I don’t think Ecuador has any legal argument that’s capable of undermining or overriding the UK’s legal obligations. If you think there are, you’re welcome to explain them. Being a refugee – even if the UK recognised Assange’s diplomatic asylum, which it doesn’t – isn’t a magic legal cloak. Asylum doesn’t make you immune from arrest all over the world.

No, I think there are no sovereignty issues involved, and I doubt any additional political pressure would be applied, if Assange were elected to the Australian Senate. I doubt Australia will be concerned enough to intervene in what are the normal workings of British and European justice. If there were any pressure, which I doubt, that would still not alter the UK’s legal obligations to Sweden.

The means of transport of the embassy is inviolate as well as the embassy itself, so all that is needed is a sedan chair down to a transit van, and thence to a chartered jet.

This is obviously correct. There is no doubt whatsoever that a sedan chair is a means of transport.

That this has not been done probably means that it suits the Government of Ecuador and Mr. Assange for him to remain in London.

On the charges: Nobody hesitated to say that the charges against Malaysia’s Anwar Ibrahim were trumped up, political charges which would not have been made were it not for who he was. Why the hesitancy here?

What ever happened to your: Carl Gardner stated that “Ecuador could name Assange as its representative to the United Nations. That would make him immune from arrest while traveling to U.N. meetings around the world”?

Carl I wanted to read the further responses before answering.

I wasn’t referring to the cost of the Met theatre outside the Ecuadorean Embassy, if that is what you mean.

I imagine there will be other costs which dwarf the pound cost of any theatrical productions.

The poker players in charge know what I mean, those cards are looking like a weaker hand every day & soon even the Q will be a 2 of clubs.

There is if course the other way you could look at it, because UK citizens are ultimately going to think Assange was a bargain at any price.

I wanted to point out the prosecutor lied about questioning abroad and said it was illegal which it is not. Also she said Assange had to be in Sweden for taking DNA samples which caused a laugh in the hearing. In 2012 she said questioning abroad is not applicable because of the EAW rules. Had she said from the beginning he could be questioned in London but for some reasons it’s not to be done it wouldn’t look so suspicious. This case is three years old. The reasons you name: fingerprints, searches, seizing documents, that’s very strange. Even in Sweden lawyers say it’s just prestige and that’s a poor reason.

—–>”Interviewing Assange other than on her own patch may disadvantage the Swedish prosecutor in ways not obvious to foreign observers – she may not be able to exercise legal powers relating to her questioning, for instance… On the point about exercising legal powers, I don’t want to speculate on the investigation of the offences Julian Assange is suspected of. I don’t think that’s in the interests of justice or of anyone involved. But taking a British example, a policeman who arrests and questions you may, because of that, have power to search you or your premises, take fingerprints or samples, seize documents and so on. It may be (I don’t know) that there are some special legal powers the prosecutor may wish to exercise that she would be unable to, were the interview conducted in an embassy in London.”

It is presumably within the bounds of diplomacy for Ecuador and Sweden to negotiate for the Swedish prosecutor all of the legal powers in a London interrogation scenario that she would otherwise have available to her in Sweden. Once the idea of questioning in London is mooted, all of these speculative reasons why the prosecutor might object become grounds for negotiation. But, as we know, the Swedish government has refused to engage on the issue.

—–>”And what guarantee would she have that following questioning he would come to Sweden for trial? Or that even if he were tried in his absence, he’d surrender himself for imprisonment, if convicted? No: it makes no sense for Sweden to agree to this. And, by the way, even if Assange agreed to serve any prison sentence in Britain – what would stop an American extradition request from ere?”

Let’s presume Assange is questioned in the embassy. Let’s presume on the basis of that interrogation, the case is dropped. In that case, the impasse is removed.

Now let’s presume on the basis of such an interrogation he is charged. Even assuming bad faith on Assange’s part, Sweden would immediately be in a stronger position vis a vis Assange and Ecuador. The decision to charge him would immediately place demands on the good faith posture Ecuador has been taking with respect to the situation. So long as it wanted to uphold its good faith posture, Ecuador would no longer have the option of offering to “facilitate questioning,” and would be forced into negotiation over the terms of a possible surrender.

Likewise, Assange himself would lose that justification, and be rhetorically obliged to engage with the process. Not that it would really matter, because the decision would be with Ecuador.

I would have assumed it was possible, under these circumstances, to arrive at an agreement whereby Assange would be surrendered to Swedish authorities for prosecution, on the condition that he would be immediately returned into the custody of Ecuador on the conclusion of proceedings (assuming he was found innocent), or on the conclusion of a possible sentence (supposing he was found guilty). It might even be mooted that he could serve a possible prison sentence in Ecuador.

This would seem to be the path of least resistance for all involved. It’s fascinating that neither you nor David Allen Green are willing to even moot these possibilities.

Fantastic post very useful info

Thanks designed for sharing such a pleasant thought, post is pleasant, thats why i have

read it fully

“@David,

Thanks.

I agree – I think questioning in Knightsbridge is a dead end, too. How could the Swedes be assured he’d surrender himself for trial, or if found guilty?”

“Sweden’s investigation into Assange had come to a halt and prosecutors’ failure to examine alternative avenues of investigation ‘is not in line with their obligation – in the interests of everyone concerned – to move the preliminary investigation forward’”—David Crouch (in Gothenburg)

Considering the above statement by the Swedish Supreme Court on the case, and the prosecutor thereafter making a point of questioning Assange in the UK, and the Swedish Ministry of Justice now negotiating to make this happen, do you (both) still regard questioning in Knightsbridge as a dead end? Or would you contend that despite activities to the contrary, the above entities and the prosecutor are not taking the questioning Assange in Knightsbridge seriously because they in all probability also believe it is a dead end?

It is interesting to note how UK speculation on the importance of questioning in Knightsbridge seems at odds with the high level activities of the Swedes to make that come about.